|

This feature is a continuation of Part Eight.

When you remove animals from danger you have to have some place to put them. Peer to peer sheltering is often a viable option. Some public facilities such as fairgrounds and rodeo grounds may have some capacity. But what if the pre-planned shelters cannot accommodate the volume of displaced animals, are impacted by the incident, or are unavailable because they are already being used for other purposes?

What if the pre-planned shelters are also impacted by the emergency and animals normally present at those facilities also require relocation?

The hard reality is that the best of plans can prove to be inadequate during a serious event. In the 1998 Contra Costa floods, all of the pre-planned shelter locations were impacted.

During a significant event, the animals could just keep on coming. Large incidents can displace literally hundreds of animals. How many and what types of animals can your pre-planned shelters reasonably handle? Can your plan adapt to an ever-increasing intake load? Can you provide sufficient volunteer staffing to accommodate large intake loads?

Public agencies will likely not have the human resources and assets needed to effectively adapt to changing conditions. Stakeholders and civilians may likely have to pick up the slack. Often the issue boils down to whether such spontaneous operations fit into a coherent local or regional plan, or whether they, due to a lack of effective pre-planning and training, have to operate "independently."

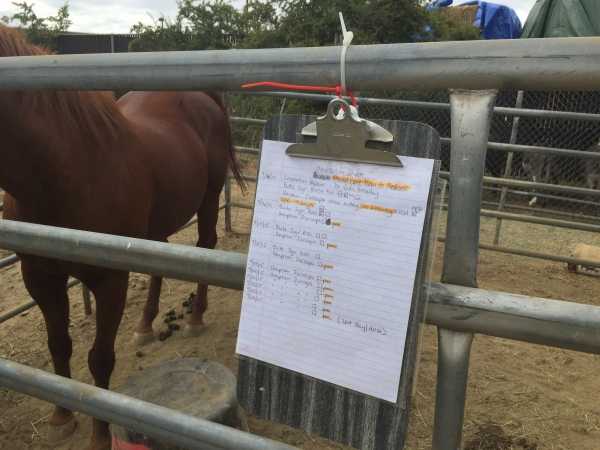

One of 800+ animals sheltered during the 2015 Butte Fire, Amador County, CA.

Whether the sheltering operation is small or large, the same planning and logistic considerations apply.

Intermediate or "waypoint" shelter locations may just require the minimum: secure fencing, water and some hay for calming, along with accurate record keeping until the animals can be relayed to more long-term shelters. Long term shelters require more in-depth planning as well as operational and logistic support.

Animals brought into long term shelters typically need:

- Proper and safe enclosures for the species being sheltered, separated as necessary to avoid conflicts.

- Adequate quantities of fresh water in appropriate containers.

- Sufficient good quality feed appropriate for the species being sheltered.

- Specialized feed as may be available for animals on prescribed special diets.

- Sanitation (enclosure cleaning) and waste removal.

- Veterinary support.

- Farrier support.

- Premises security / access control / bio-security.

- A disposal plan for any intake animals that die or have to be euthanized.

- Sufficient competent volunteers to provide care for and monitor the animals and maintain records.

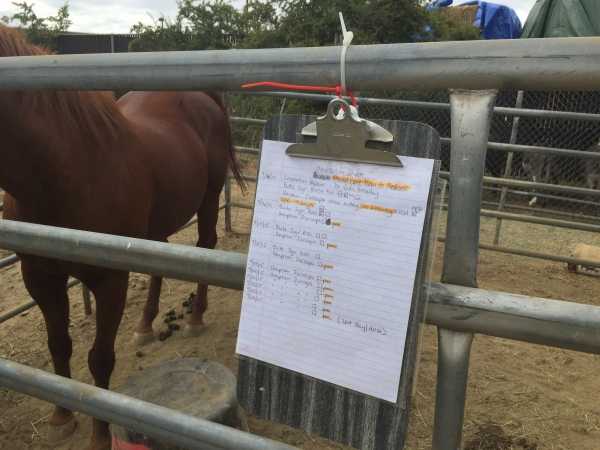

- Maintenance of complete records on each animal that indicates its location of origin, owners (if known,) condition when found, any veterinary medical issues (if known,) and the animal's disposition when finally recovered by its owner or authorized agent, or if the animal is deceased.

- Public information strategies, such as using social media and accurate press releases to inform the public as to sheltering availability as well as the needs for loaned equipment and donated supplies in order to support the sheltering operation. Such strategies should include careful consideration of actual message content and designating who will do the messaging. Such planning is important in order to maintain accuracy and consistency in the information being disseminated.

In expanding and larger operations, adequately addressing all of these issues requires significant volunteer commitment, practical organization, division and assignments of responsibilities, and scheduling of relief personnel.

By the very nature of the emergency, some animals may arrive having significant need of qualified veterinary attention. Rescuers in the field will generally not have time to evaluate animals in the middle of "load and go" evacuation operations. Some consideration must be given to competently evaluating animals as they are taken in.

In looking at the practical side of long term sheltering, there can be some disconnect between official public agency policies and real events, particularly during rapid onset emergencies and incidents that expand beyond expectations. Rapidly changing events can challenge even the most thorough planning efforts. Nonetheless, volunteer-driven sheltering operations should strive to follow state and locally established protocols as much as possible. Thus anyone contemplating the possibility of organizing an emergency shelter should be familiar with state and local planning documents. Conformance with established protocols helps ensure interoperability with state and local efforts and can provide connectivity with potentially available local and state resources.

Another planning resource that potential shelter operators should download and have on hand is

Emergency Animal Sheltering Best Practices, published by the National Alliance of State Animal and Agricultural Emergency Programs. This document provides a broad spectrum of information ranging from pre-incident planning to sustaining an effective long-term shelter.

The Laughton Ranch sheltering operation, staffed entirely by volunteers, provides a credible example of sound "spontaneous" sheltering operations. This operation sprang up when officially designated shelters found themselves exponentially overwhelmed.

Different species have different sheltering requirements.

The arrival of small animals of various species with specific needs also must be considered.

Animals may be received that were injured during the incident.

Arrangements should be made for providing proper veterinary care.

Charts need to be maintained for all animals undergoing veterinary treatment.

Some animals may have allergies or dietary issues.

Some animals may have behavioral issues that warrant warnings to volunteers.

Animals that were known to get along well together were turned out into

larger areas. In this case a water tender delivered clean water to remote tanks.

Supplies including hay, stock tanks and animal crates came from as far away as Nevada.

Animal evacuation and sheltering operations should be organized with the same

mutual aid considerations as fire/rescue operations. (NDF crews at a CA fire.)

|

|

Additional Sheltering Considerations

|

Various sheltering issues should be preplanned and protocols developed.

- Who will provide equipment and supplies for shelter operations. (NGOs, local authorities?)

- Where equipment and supplies will be stored that is secure, and who will be charged with transport to and from the shelter site(s).

- Who is in charge of the initial layout and set-up of the shelter.

- Who is in charge of making arrangements to use the shelter site and announcing the location of the shelter to the public.

- Who is in charge of making necessary legal agreements with the owner of the shelter site.

- Who will provide the personnel for shelter management and operations. (Will shelter management also coordinate field evacuation operations?)

- Identification of existing organizations or entities where these trained volunteers can be affiliated for fundraising / donations, some form of disaster responder insurance, etc.

- Compiling and maintaining lists of various “as needed” resources related to animals in disasters such as veterinarians, farriers, sources for animal feed and other equipment and supplies for field or shelter operations. (Who will create and maintain those lists in the emergency plan?)

- How field and shelter management would have the authority to make direct contact to arrange for services or supplies, including meals for volunteers working shifts, billed to the operational area. (What is the process?)

- Shelters should be located where they aren't likely to be impacted by anticipated emergencies. Alternative locations should be identified in the event the designated primary shelters become impacted by significant events.

- Shelters should preferably be located where there is reliable road access from more than one direction to reduce traffic congestion, and to reduce the potential for that location to become isolated by a road closure.

- Shelters should be adaptable and expandable as incident needs dictate.

- Shelters should have the ability to establish and maintain access control.

- Space and layouts need to be considered for vehicle use, not just shelter capacity. For example, shelters should have adequate parking for rotating staff and visitors (animal owners, supply deliveries, etc.), and provide large vehicle access with turn-around space to accommodate trucks and trailers, service vehicles, etc. Additional vehicles or large equipment needed for shelter operations may also need parking space. The layout of holding pens should be spaced to allow transport trailer access and egress for unloading difficult animals directly into suitable enclosures, and later for loading directly into a trailer for departure. Wide aisle access also allows for motorized access to deliver feed and water, to collect manure, etc.

- Shelters should be located proximate to qualified volunteers. If such is not the case, potential volunteers proximate to pre-planned shelters should be recruited and trained.

- Shelters should have accommodations for on-site volunteer rest and rehab, restroom facilities, etc. If such facilities are not present, resources that could be brought in should be identified and arrangements made for delivery.

- Stakeholder and citizen or NGO-based sheltering plans should be coordinated with local authorities, preferably through pre-planning meetings. Such pre-planning can be critical in maximizing shelter efficiency and preventing conflicts that could disrupt effective operations.

- A standardized temporary facility use agreement could be useful to establish consistent expectations.

|

|

Spontaneous Volunteers at Shelters

|

- Local resources are likely to be overwhelmed early by a larger disaster. Local volunteers may or may not have the background, training and experience to successfully open and manage a large animal shelter. Equipment and supplies are needed from pre-identified sources as delivery and resupply will be needed for some items. Someone knowledgeable needs to design the scalable layout of temporary shelter facilities, preferably as a preplan. Someone knowledgeable needs to manage the shelter operations, communicate and coordinate within the incident command structure, maintain a variety of records, and arrange for personnel to perform tasks with supervision as needed. Staffing is needed to provide for 24/7 shift work and labor for a multitude of tasks. While trained volunteers may be available to work in shifts, odds are that additional personnel will be needed, particularly during the days when shelter operations are more labor intensive. The additional labor force will likely need to come from the community as spontaneous volunteers.

- Processes need to be in place regarding use of spontaneous volunteers at the large animal shelter. Forms are needed to document the identity of each person, interviews will determine what kind of tasks that volunteer might be suited to perform and what basic training may be warranted. A legal waiver or other documents such as designating volunteer disaster service worker status should be included. It might develop that an applicant would be more suited for small animal shelter operations or other tasks, and can be referred to such operations.

- Once “in the system” each volunteer would need to sign in and sign out whenever assisting at the shelter so accurate shelter personnel records are maintained. For site security, issuing a daily temporary ID of some type would be advisable. Shelter management might choose to set up a schedule where volunteers can sign up to work a particular block of time, trying to adjust staffing to meet needs during various time frames.

- Some of those spontaneous volunteers may be the actual owners of large animals sheltered there, and those owners might be recruited to perform daily tasks to help care for their own animals while they are reminded to seek a private arrangement for longer term sheltering of their animals should it be required.

- Large animal evacuation and shelter planning should have a preplan for use of spontaneous volunteers. Useful and reliable spontaneous volunteers could ultimately be recruited to join the trained volunteer organization, strengthening the response capability of that resource. Every volunteer – trained or otherwise – will also bring personal knowledge and skill sets that could be useful in a variety of capacities and have potential to be tapped by the sheltering organization or serve the operational area's needs.

- If there is a demand for community volunteer assistance, the operational area can choose to set up an Emergency Volunteer Center and notify the public. That volunteer center would collect requests for volunteers having certain skill sets, then processes the various spontaneous volunteers to respond to where the request for assistance needing their skill set was generated. For example, such a process might match spontaneous volunteers with confirmed health care backgrounds to local hospitals or senior care facilities, match folks needing heavy equipment operators or licensed bus drivers, send labor where labor is needed, plumbers, electricians, mechanics, general office work, certain computer skills, folks experienced with small or large animals, etc., who can all provide their assistance as volunteers. Categories would vary depending on evolving local needs.

- If a large number of volunteers are needed in an area with limited parking, consider arranging a staging area with volunteers being transported by bus or organized car pools.

- Setting up an Emergency Volunteer Center requires some preplanning for communications, processes and staffing, but in a larger disaster where community help is needed, an EVC can make the best use of spontaneous volunteers by matching skill sets with local needs.

© 2017 Least Resistance Training Concepts. All rights reserved.

Permission to use content and images for non-commercial purposes.

|